In this blog series, I will explain how to develop your own Chromium fork with fingerprint mimicry.

Our goal is to be able to edit basic fingerprints, like the user-agent, the CPU core counts, but also more complicated entropy sources such as canvas fingerprinting.

So, you’ve now downloaded and compiled Chromium for the first time.

Now, we are going to focus on creating a first patch — nothing fancy; just something that will allow you to spoof your user-agent by passing a special environment variable while starting Chromium.

Where is “native code” stored?

If you’ve ever worked on a web development project, you probably accidentally asked for the definition of a native function.

For example, if you type document.querySelector, Chromium returns the following function definition:

ƒ querySelector() { [native code] }

Hm… mysterious. Can we see this native code?

In the same way, accessing navigator.userAgent triggers a C++ getter inside the Chromium codebase that generates and returns the result

you are looking for. userAgent is not actually a variable that you can modify.

It’s C++ all the way down.

Finding the source code of a JS function: document.querySelector

I think that it’s better to let the Chrome docs explain what IDL files are:

Web IDL is a language that defines how Blink interfaces are bound to V8. You need to write IDL files (e.g. xml_http_request.idl, element.idl, etc) to expose Blink interfaces to those external languages. When Blink is built, the IDL files are parsed, and the code to bind Blink implementations to V8 interfaces automatically generated.

IDL is a language that defines bindings, which allow exposing functionality from C++ into the JavaScript environment.

Let’s hunt for the IDL file that defines document.querySelector:

rg -l "querySelector" -g "*.idl" ./src/chromium/srcWe get the following list of files:

./src/chromium/src/third_party/blink/renderer/core/dom/parent_node.idl./src/chromium/src/third_party/blink/web_tests/external/wpt/interfaces/dom.idlWe can skip the web_tests one.

Here is the content of parent_node.idl:

// https://dom.spec.whatwg.org/#interface-parentnodeinterface mixin ParentNode { [SameObject, PerWorldBindings] readonly attribute HTMLCollection children; [PerWorldBindings] readonly attribute Element? firstElementChild; [PerWorldBindings] readonly attribute Element? lastElementChild; readonly attribute unsigned long childElementCount;

[Unscopable, RaisesException, CEReactions] undefined prepend((Node or DOMString or TrustedScript)... nodes); [Unscopable, RaisesException, CEReactions] undefined append((Node or DOMString or TrustedScript)... nodes); [Unscopable, RaisesException, CEReactions] undefined replaceChildren((Node or DOMString or TrustedScript)... nodes); [CEReactions, PerWorldBindings, RaisesException, MeasureAs="WebDXFeature::kMoveBefore"] undefined moveBefore(Node node, Node? child);

[Affects=Nothing, RaisesException] Element? querySelector(DOMString selectors); [Affects=Nothing, NewObject, RaisesException] NodeList querySelectorAll(DOMString selectors); [RuntimeEnabled=DocumentPatching, CallWith=ScriptState, RaisesException] WritableStream patchSelf(); [RuntimeEnabled=DocumentPatching, CallWith=ScriptState, RaisesException] WritableStream patchBetween(Node prev_child, Node next_child); [RuntimeEnabled=DocumentPatching, CallWith=ScriptState, RaisesException] WritableStream patchAfter(Node ref); [RuntimeEnabled=DocumentPatching, CallWith=ScriptState, RaisesException] WritableStream patchBefore(Node ref); [RuntimeEnabled=DocumentPatching, CallWith=ScriptState] WritableStream patchAll();};Hm… no C++ code.

What if we look for references to that file?

Well, if we look closely in the docs, we can read this:

The Web IDL spec treats the Web API as a single API, spread across various IDL fragments. In practice these fragments are .idl files, stored in the codebase alongside their implementation, with basename equal to the interface name.

Thus for example the fragment defining the Node interface is written in node.idl, which is stored in the third_party/blink/renderer/core/dom directory, and is accompanied by node.h and node.cc in the same directory.

In some cases the implementation has a different name, in which case there must be an [ImplementedAs=…] extended attribute in the IDL file, and the .h/.cc files have basename equal to the value of the [ImplementedAs=…].

We cannot find a parent_node.cc file, though.

However, we can find that other idl files include our ParentNode mixin.

cami@onigiri ~/c/r/s/c/s/t/b/r/c/dom> rg "includes ParentNode"document_fragment.idl31:DocumentFragment includes ParentNode;

element.idl192:Element includes ParentNode;

document.idl244:Document includes ParentNode;Remember? We were interested in document.querySelector in particular.

Is there a .cc file for Document? Yes, there is!

… but no implementation of querySelector can be found there.

However, we notice in document.h that Document inherits from ContainerNode:

class CORE_EXPORT Document : public ContainerNode, public TreeScope, public UseCounter, public WidgetCreationObserver { DEFINE_WRAPPERTYPEINFO();

// ... snip ...}And when we read container_node.cc, we find this:

Element* ContainerNode::querySelector(const AtomicString& selectors, ExceptionState& exception_state) { return QuerySelector(selectors, exception_state);}

Element* ContainerNode::QuerySelector(const AtomicString& selectors, ExceptionState& exception_state) { SelectorQuery* selector_query = GetDocument().GetSelectorQueryCache().Add( selectors, GetDocument(), exception_state); if (!selector_query) return nullptr; return selector_query->QueryFirst(*this);}Now we’re talking!

So, to recap:

.idlfiles contain the blueprint for the JS environment in Chrome- These are implemented by

.ccfiles directly next to them - But there are a bunch of includes and class inheritance that sometimes make it a bit tricky to find the exact code we’re interested in.

You cannot just “follow references” from an IDL file; you’ve got to do a little bit of detective work.

Well. You could just stay in src/third_party/blink/renderer/core/dom and use ripgrep to find the function definition directly:

cami@onigiri ~/c/r/s/c/s/t/b/r/c/dom> rg "querySelector\("README.md158:const b = document.querySelector('#B');217:[`TreeOrderedMap`](./tree_ordered_map.h), so that `querySelector('#foo')` can219:`root.querySelector('#foo')` can be slow if it is used in a node tree whose

document_test.cc482: "document.querySelector('input').reportValidity(); };");

container_node.h100: Element* querySelector(const AtomicString& selectors, ExceptionState&);

container_node.cc1510:Element* ContainerNode::querySelector(const AtomicString& selectors,

parent_node.idl43: [Affects=Nothing, RaisesException] Element? querySelector(DOMString selectors);

element.h2537: // doesn't exist, and used to accelerate querySelector() (can quicklyYou can quickly eliminate candidates:

- README.md: obviously not

- document_test.cc: testing code, and besides, it’s JavaScript

- parent_node.idl: that’s the IDL file, not the actual code

- element.h: this is part of a comment

The rest (container_node.h and container_node.cc) correspond to the actual code we’re interested in.

Writing a patch for navigator.userAgent

Alright. Now that we know how to find the source code of a JS attribute/function in Chromium,

let’s actually patch navigator.userAgent.

Finding where navigator.userAgent is defined

Let’s do a simple ripgrep search, like true greybeards, this time:

cami@onigiri ~/c/r/s/c/s/t/b/r/c/dom [1]> rg "userAgent"hm… what? No results!

Looks like we are in the wrong place. Let’s take a step back by going into the root of the Chromium source code and searching for mentions of “userAgent”

in any .idl file:

cami@onigiri ~/c/r/s/c/s/t/b/r/c/dom > cd ../../../../../cami@onigiri ~/c/r/s/c/src> rg "userAgent" -g "*.idl"third_party/blink/renderer/core/frame/navigator_ua.idl8: [SecureContext] readonly attribute NavigatorUAData userAgentData;

third_party/blink/renderer/core/frame/navigator_id.idl41: [MeasureAs=NavigatorUserAgent] readonly attribute DOMString userAgent;

third_party/blink/renderer/modules/credentialmanagement/digital_credential.idl18: static boolean userAgentAllowsProtocol(DOMString protocol);

third_party/blink/web_tests/external/wpt/interfaces/html.idl2406: readonly attribute DOMString userAgent;

third_party/blink/web_tests/external/wpt/interfaces/ua-client-hints.idl41: [SecureContext] readonly attribute NavigatorUAData userAgentData;

third_party/blink/web_tests/external/wpt/interfaces/digital-credentials.idl37: static boolean userAgentAllowsProtocol(DOMString protocol);From these results, we figure out that the JS userAgent attribute is defined in third_party/blink/renderer/core/frame/navigator_id.idl.

We cd into third_party/blink/renderer/core/frame/ and try searching for the definition of userAgent in C++ code again:

cami@onigiri ~/c/r/s/c/s/t/b/r/c/frame> rg "userAgent" -g "*.cc"navigator_ua_data.cc118: // client hints returned by navigator.userAgentData.getHighEntropyValues(),

navigator_id.cc57: const String& agent = userAgent();

navigator_ua.cc14:NavigatorUAData* NavigatorUA::userAgentData() {Okay, we’re getting somewhere. Remember? Our .idl file is called navigator_id.idl, and now, we see some kind of access to a userAgent() function in navigator_id.cc.

We open navigator_id.cc, and find something pretty disappointing:

String NavigatorID::appVersion() { // Version is everything in the user agent string past the "Mozilla/" prefix. const String& agent = userAgent(); return agent.Substring(agent.find('/') + 1);}We can see a usage of userAgent, yes, but no definition!

I assume here that you set up clangd to be able to go to reference, etc. I’ll probably make a post about it (I just couldn’t help but start writing

about patching right away!). In the meantime, you can look at the official Chromium documentation.

We’re going to take advantage of the LSP server.

I press gd in my editor to go to the definition of userAgent, which makes us land in navigator_id.h.

namespace blink {

class CORE_EXPORT NavigatorID { public: String appCodeName(); String appName(); String appVersion(); virtual String platform() const; String product(); virtual String userAgent() const = 0; // <---- our cursor jumps to this line};

} // namespace blinkUh-oh… userAgent is a virtual function. That can’t be good.

Once again, the clangd LSP server will save us.

I put my cursor on userAgent and type gi to get the list of implementations.

Surprisingly, there is only one, in navigator_base.cc. Right.

Here is how it looks:

String NavigatorBase::userAgent() const { ExecutionContext* execution_context = GetExecutionContext(); return execution_context ? execution_context->UserAgent() : String();}Bingo!

Hardcoding the value of navigator.userAgent

Let’s inject our user agent with some unholy C++:

String NavigatorBase::userAgent() const { return String("foobar"); // ExecutionContext* execution_context = GetExecutionContext(); // return execution_context ? execution_context->UserAgent() : String();}Then, we build Chromium. Grab some popcorn, because that’ll likely take a few minutes at least…

# if you don't have a justfile defined, read the last post to get started :)just buildOne eternity later, the build completes:

ninja: Entering directory `out/Default' 1.80s load build.ninjabuild finishedlocal:175 remote:0 cache:0 cache-write:0(err:0) fallback:0 retry:0 skip:129390fs: ops: 20150(err:17854) / r:1148(err:0) 55.08GiB / w:110(err:0) 83.14MiB resource/capa used(err) wait-avg | s m | serv-avg | s m | pool=link/1 110(0) 4m39.75s |▂ ▂▂▂█ | 4.42s | ▂█▂ |8m16.89s Build Succeeded: 175 steps - 0.35/sLet’s open our compiled binary with our dedicated command:

just openA freshly baked Chromium window appears.

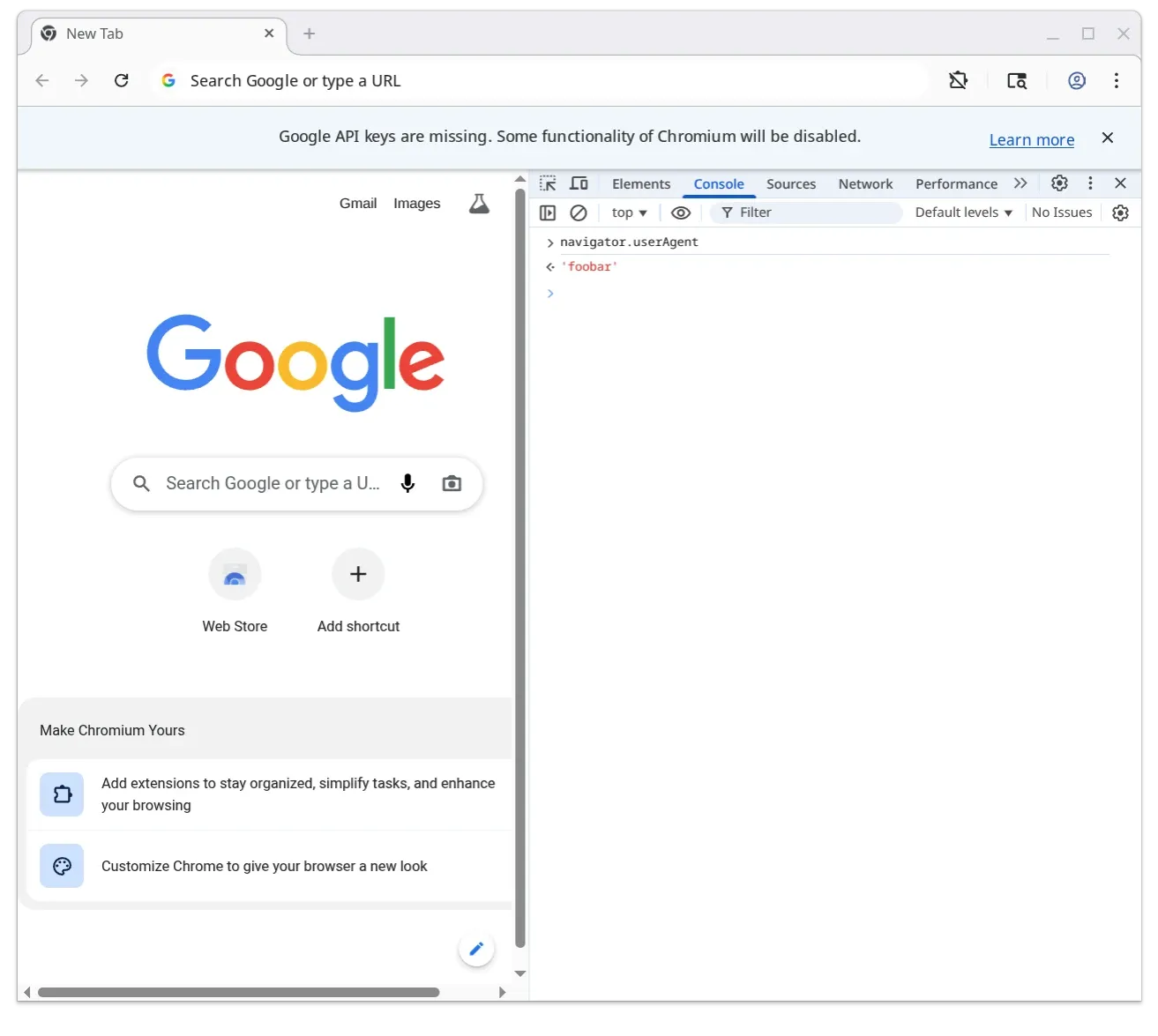

Let’s open DevTools and type navigator.userAgent…

… success! We can see that our navigator.userAgent got spoofed correctly!

Using an environment variable to define the user-agent

Now, let’s make it a bit better by using an environment variable, which will allow us to inject the value we want before starting the browser:

String NavigatorBase::userAgent() const { // START OF PATCH const char* fp_user_agent = std::getenv("FP_USER_AGENT"); if (fp_user_agent) { return String::FromUTF8(fp_user_agent); } // END OF PATCH

ExecutionContext* execution_context = GetExecutionContext(); return execution_context ? execution_context->UserAgent() : String();}We build and open Chromium:

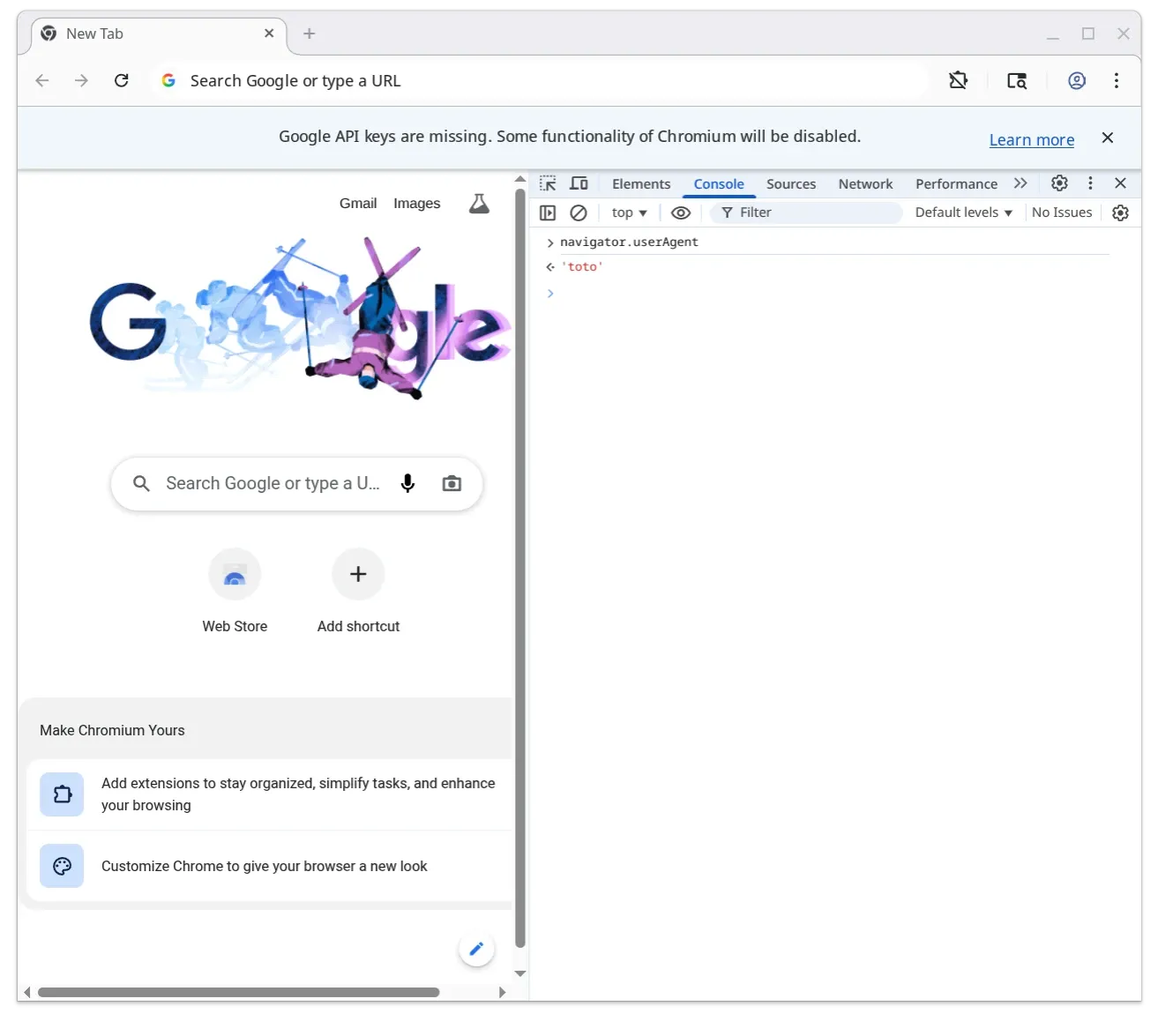

just build-fastFP_USER_AGENT=toto src/chromium/src/out/Default/chromeAnd then we type navigator.userAgent in DevTools:

As you can see, the value we put in FP_USER_AGENT got applied successfully.

Generating the patchfile

Once you’ve got a tweak that works well for your purpose, you’ll likely want to preserve it for later use.

For this purpose, we’ll use good old patch files.

Why use patch files instead of git branches?

Using commits on top of the actual Chromium repo is impractical because

you would need to find a git host that would host dozens of gigabytes of code. Then, you would need to learn

and tweak the whole dependencies syncing system (gclient sync) to work with forks of the various components that

you’ll patch.

I am sure that working with pure git is cleaner, but I am not sure that I would ever recoup the time investment involved in getting it working. Also, I’ve tried patch files, and they just work, save for the occasional line numbers change that can be delegated to Claude Code for the most part anyway.

Justfile command

Here’s the just command that I’m using to generate the patch files:

# Generate a patch from a modified chromium file (fzf selection)gen-patch-fzf: #!/usr/bin/env bash set -e cd src/chromium/src selected=$(git diff --name-only | fzf --preview 'git diff {}') if [[ -z "$selected" ]]; then echo "No file selected" exit 1 fi

# Determine output directory based on path if [[ "$selected" == third_party/blink/* ]]; then outdir="../../../patches/blink" elif [[ "$selected" == chrome/* ]]; then outdir="../../../patches/chrome" else outdir="../../../patches/other" mkdir -p "$outdir" fi

filename=$(basename "$selected") git diff -- "$selected" > "$outdir/${filename}.patch" echo "Wrote $outdir/${filename}.patch"Generating the patch file

When running it, you’ll get a fzf (fuzzy finding) window that lists all the modified Chromium source files.

You can type to search the one that you want to generate a patch file for.

Once you press enter, it’ll write a file in ./patches/blink/.

There are obviously many ways to handle this; for example, you could create a command that generates patch files for all the modified files in the git folder rather than requiring you to manually create a patch each time you make a modification.

I enjoy this manual approach more than an automated one for now, but might change my mind later.

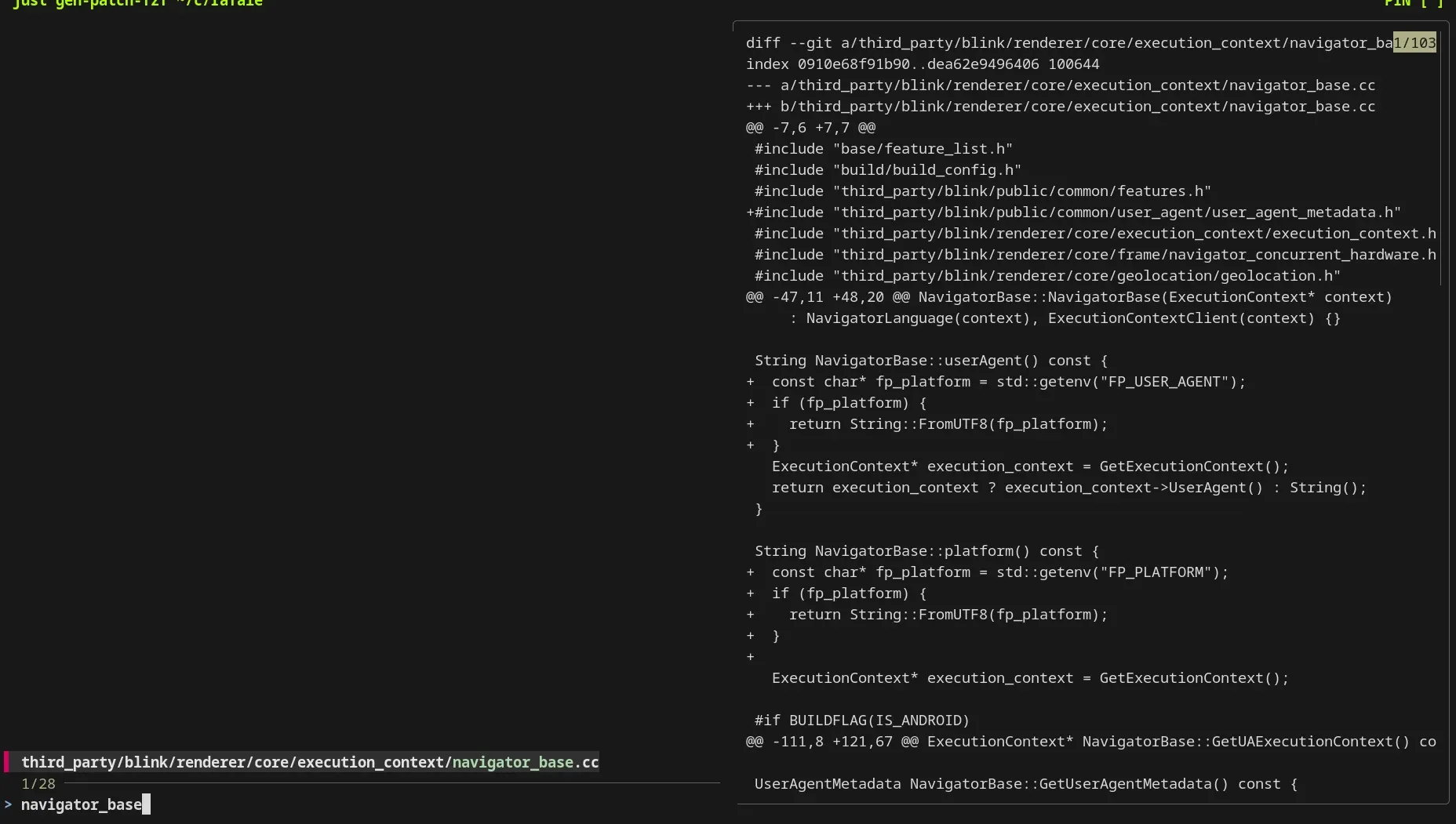

Here is the end result:

diff --git a/third_party/blink/renderer/core/execution_context/navigator_base.cc b/third_party/blink/renderer/core/execution_context/navigator_base.ccindex 0910e68f91b90..dea62e9496406 100644--- a/third_party/blink/renderer/core/execution_context/navigator_base.cc+++ b/third_party/blink/renderer/core/execution_context/navigator_base.cc@@ -47,11 +48,18 @@ NavigatorBase::NavigatorBase(ExecutionContext* context) : NavigatorLanguage(context), ExecutionContextClient(context) {}

String NavigatorBase::userAgent() const {+ const char* fp_user_agent = std::getenv("FP_USER_AGENT");+ if (fp_user_agent) {+ return String::FromUTF8(fp_user_agent);+ } ExecutionContext* execution_context = GetExecutionContext(); return execution_context ? execution_context->UserAgent() : String(); }

String NavigatorBase::platform() const {+ const char* fp_platform = std::getenv("FP_PLATFORM");+ if (fp_platform) {+ return String::FromUTF8(fp_platform);+ }+ ExecutionContext* execution_context = GetExecutionContext();

#if BUILDFLAG(IS_ANDROID)As you can see, there is a bonus patch for navigator.platform included.

Applying the patch before building

Here is the justfile command that I’m using for building:

build: patch build-chromium-builder # ... snip ...As you can see, it depends on the patch command, that is defined here:

patch: patch-args patch-patchesI’ll skip patch-args for now and focus on patch-patches:

# Patch all the non-skipped patchfiles in parallel.patch-patches: #!/usr/bin/env bash set -e find patches -name "*.patch" ! -name "*.skip" | xargs -P {{build_threads}} -I {} just patch-patch {}This command:

- Finds the patch files

- Excludes the ones that end in

.skip - Calls

just patch-patchfor each of those in parallel

# Apply a given patch file (uses patch command instead of git for parallel safety)patch-patch patchpath: #!/usr/bin/env bash set -e

# Path of the file we want to patch. target_path=$(grep "^---" {{patchpath}} | head -n 1 | awk '{print $2}' | sed -e 's|^a/||')

cd src/chromium/src

# Save current content hash and mtime before patching current_hash=$(sha256sum "$target_path" | cut -d' ' -f1) current_mtime=$(stat -c %Y "$target_path")

# Reset the file by reading from git HEAD (doesn't lock git index) git show "HEAD:$target_path" > "$target_path"

# Apply the patch using patch command (works on files directly, no git lock) patch -p1 < ../../../{{patchpath}}

# If content is the same as before, restore original mtime to preserve build cache new_hash=$(sha256sum "$target_path" | cut -d' ' -f1) if [[ "$current_hash" == "$new_hash" ]]; then touch -d "@$current_mtime" "$target_path" echo "Applied {{patchpath}} (already applied, mtime preserved)" else echo "Applied {{patchpath}}" fijust patch-patch applies a single patch that’s been specified as an argument.

- We extract the target path of the file to patch from the patch’s header

- We compute the hash + get the mtime of the target file

- We reset the file in git — we do that by reading the file at the HEAD rather than using

git checkout, to save time (git can be slow in a codebase of this size) - We apply the patch

- If the file didn’t get modified, we put back the mtime we saved earlier. This helps with build caching.

That’s it!

Why this patch is not enough

The patch we just wrote only allows us to inject our user agent in navigator.userAgent; it doesn’t change the actual user-agent header

that gets sent over the network.

This is obviously an issue; you’ll need to dig into how HTTP requests are made in Chromium, then pull the thread until you figure out a convenient place where

you could inject the value of FP_USER_AGENT.

You’ll also need to update navigator.userAgentData for it to be consistent.

You will need to painstakingly write dozens of patches to fully control your fingerprint while still being consistent.

End note

I hope that this post helped you get a better idea of what patching Chromium looks like.

As you can see, it’s not totally impossible, but there can be some frustrating issues, especially if you don’t know C++.

For example, I struggled for a bit too long to figure out a way to convert a const char* into a String.

What’s next?

I’ll probably talk about setting up clangd or mold for faster linking times.